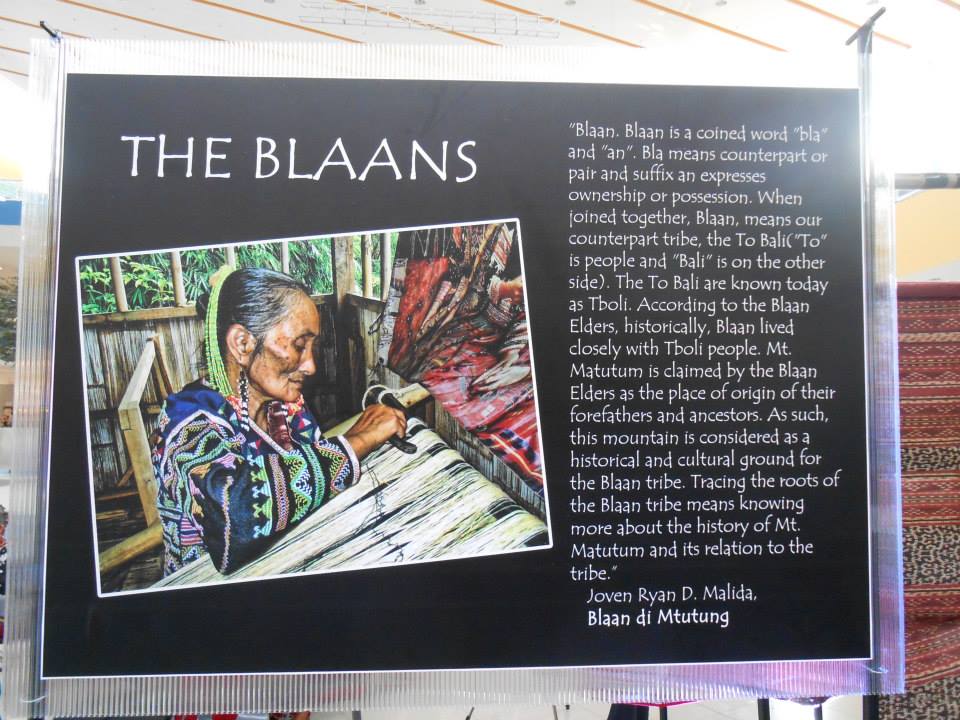

Blaan definition & importance of Mt. Matutum

Blaan History and the Lamlifew Village

Photo credit: Jordi Llorens Estape, 2005

A distinct Blaan society was recorded in 19th century missionary, traveler, and scientific accounts of southern underbelly of the Philippine island of Mindanao. Notably, the Czech Filipinologist Ferdinand Blumentritt inscribed the Blaan as a separate cultural group; as did the American anthropologists who visited the Davao Gulf area in the early decades of the 21st century.

As typical of these early accounts, the data focused on differentiations in clothing, weaponry, ritual and other facets of culture, between and among groups collectively referred to as "wild tribes".These early documents also indicated substantial sharing of mythic and material culture traditions in this region, which until the mid-20th century, was a vast province named for a large pre-Hispanic settlement, Kuta Batu; i.e., Cotabato. The peoples now known as Blaan seem to have lived in coastal (Sarangani Bay) as well as interior zones for centuries; have witnessed the Islamization of the coastal populations during the last 400 years, and seen the consolidation of Muslim society around the mouth of the Buayan River; and had to cope with the impact of of Christianization and migration from Luzon and the Visayas, from the early 20th century. A specifically Protestant missionary effort played out early among the Sarangani Blaan of the coastal areas - as a result of which, there are many Christian Blaan-speakers today who have little or no connection with the traditional Blaan culture. In the latter quarter of the 20th century, the Blaan communities have been absorbed into the collective political designation "lumad", together with all of Mindanao's other marginalized peoples.

Nonetheless, there remain highland villages in their original homeland, where Blaan identity survives to the 21sth century. An example are the villagers of Lamlifew, who have a two-part knowledge: firstly, the solid understanding of the beliefs, norms, and material culture of their grandparents (who lived in the early 20th and late 19th centuries); and secondly, a firm and clear-eyed understanding of the changes endured or embraced by the generations who lived through the 20th century. They recall, for example, the measures of quality and the distinct weaving patterns of the ikat-dyed lutay (Musa textilis Nee) before the degeneration of this knowledge. But they also recognize what constitutes the degeneration. They are able to retrieve lore surrounding traditional food crops and medicinal herbs, but are also able to narrate how this knowledge was eroded. They are able to create a museum that works within the community as a setting for story-telling, so that the younger villagers can provide the laughter, interest, and enthusiasm to tease out data from the minds of grandparents. And they are able to enjoy making new songs out of ancient musical conventions, using instruments such as gongs whose origins predate the arrival of Islam and Christianity into Mindanao. With these gongs - as well as wooden instruments that have never been documented in ethnomusicology - they weave together the past and the future.

Source: Notes from Marian Pastor Roces and IPDP flyer on Lamlifew Village Museum

As typical of these early accounts, the data focused on differentiations in clothing, weaponry, ritual and other facets of culture, between and among groups collectively referred to as "wild tribes".These early documents also indicated substantial sharing of mythic and material culture traditions in this region, which until the mid-20th century, was a vast province named for a large pre-Hispanic settlement, Kuta Batu; i.e., Cotabato. The peoples now known as Blaan seem to have lived in coastal (Sarangani Bay) as well as interior zones for centuries; have witnessed the Islamization of the coastal populations during the last 400 years, and seen the consolidation of Muslim society around the mouth of the Buayan River; and had to cope with the impact of of Christianization and migration from Luzon and the Visayas, from the early 20th century. A specifically Protestant missionary effort played out early among the Sarangani Blaan of the coastal areas - as a result of which, there are many Christian Blaan-speakers today who have little or no connection with the traditional Blaan culture. In the latter quarter of the 20th century, the Blaan communities have been absorbed into the collective political designation "lumad", together with all of Mindanao's other marginalized peoples.

Nonetheless, there remain highland villages in their original homeland, where Blaan identity survives to the 21sth century. An example are the villagers of Lamlifew, who have a two-part knowledge: firstly, the solid understanding of the beliefs, norms, and material culture of their grandparents (who lived in the early 20th and late 19th centuries); and secondly, a firm and clear-eyed understanding of the changes endured or embraced by the generations who lived through the 20th century. They recall, for example, the measures of quality and the distinct weaving patterns of the ikat-dyed lutay (Musa textilis Nee) before the degeneration of this knowledge. But they also recognize what constitutes the degeneration. They are able to retrieve lore surrounding traditional food crops and medicinal herbs, but are also able to narrate how this knowledge was eroded. They are able to create a museum that works within the community as a setting for story-telling, so that the younger villagers can provide the laughter, interest, and enthusiasm to tease out data from the minds of grandparents. And they are able to enjoy making new songs out of ancient musical conventions, using instruments such as gongs whose origins predate the arrival of Islam and Christianity into Mindanao. With these gongs - as well as wooden instruments that have never been documented in ethnomusicology - they weave together the past and the future.

Source: Notes from Marian Pastor Roces and IPDP flyer on Lamlifew Village Museum